This is a brief notebook, but it is heavily reliant on the concepts covered in the Single Lens notebook. If you have not completed that notebook, perhaps it would be best if you did that and then came back.

If you haven't already done so, install MulensModel before continuing with this notebook:

pip install MulensModel

# package imports (SHIFT + ENTER to run)

import numpy as np

import emcee

import MulensModel as mm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import multiprocessing as mp

from IPython.display import display, clear_output

from typing import List, Tuple, Optional, Union

# dev note: replace emcee with dynesty?

The binary source model#

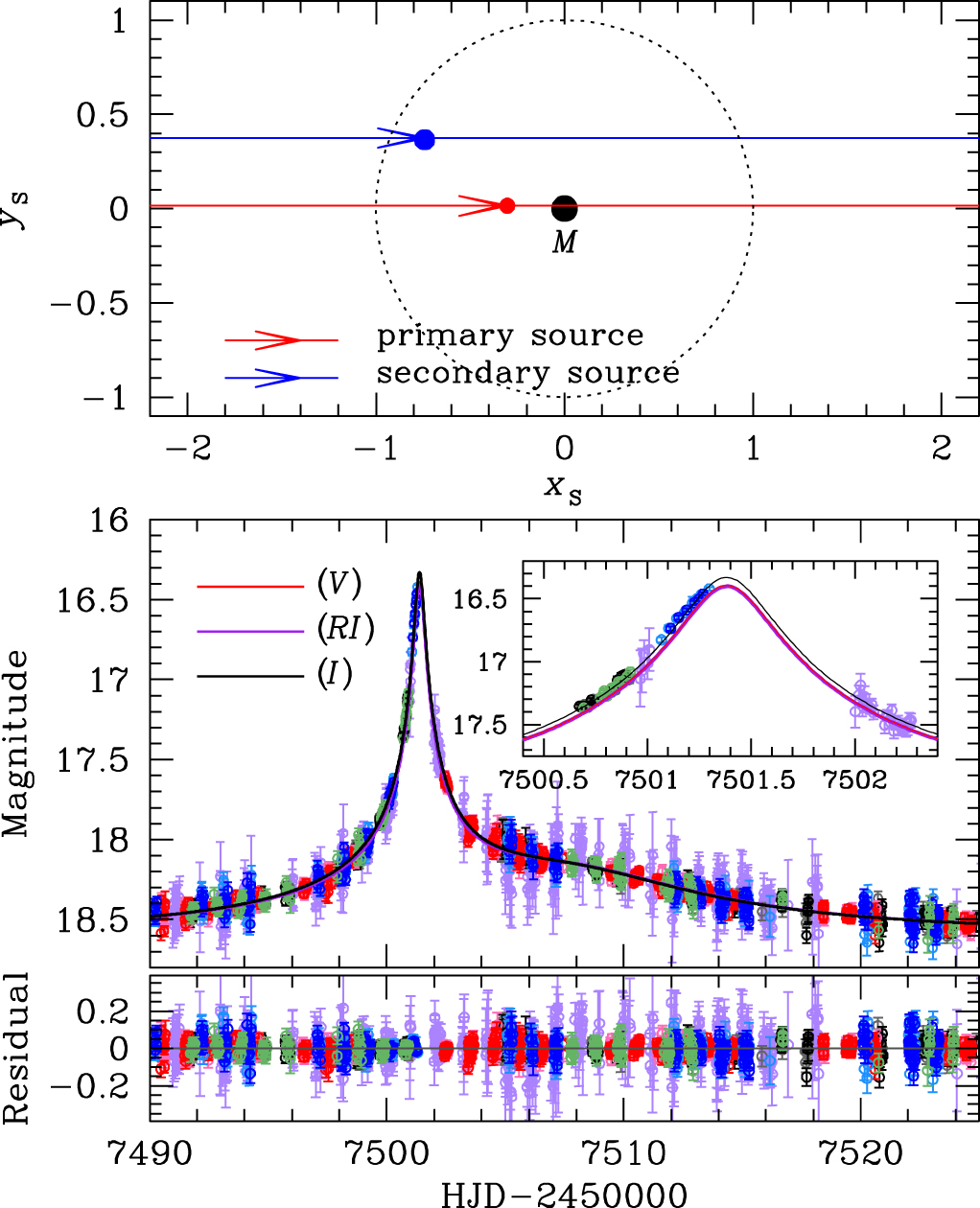

Events matching a one-lens, two-sources model typically have lightcurves with smooth non-Paczynski shapes, such as the one in Jung et al. (2017), Figure 5, which is shown below (event OGLE-2016-BLG-0733). They are, in effect, two distinct Paczynski curves on top of each other; they do not create "sharp" perturbations from the primary Paczynski curve, like the binary-lens models typically do.

|

|

|---|---|

[Reproduction of Jung et al. (2017), Figure 5] Geometry and lightcurve of the binary-source model. Top: The upper panel shows the geometry of the binary-source model. Two straight lines with arrows are the source trajectories of individual source stars. The lens is located at the origin (marked by M), and the dotted circle is the angular Einstein ring. The red and blue filled circles represent the individual source positions at $\rm{HJD}'=7497$. Lengths are normalised by the Einstein radius. Bottom: The lower panel shows the enlarged view of the anomaly region. The two curves with different colours are best-fit binary-source models for $RI$ and $I$ passbands. The inset shows a zoom of the anomaly near $\rm{HJD}'\sim7501.4$. We note that, although we only use the $V$-band data for determining the source type, we also present the $V$-band model lightcurve to compare the colour change between passbands. |

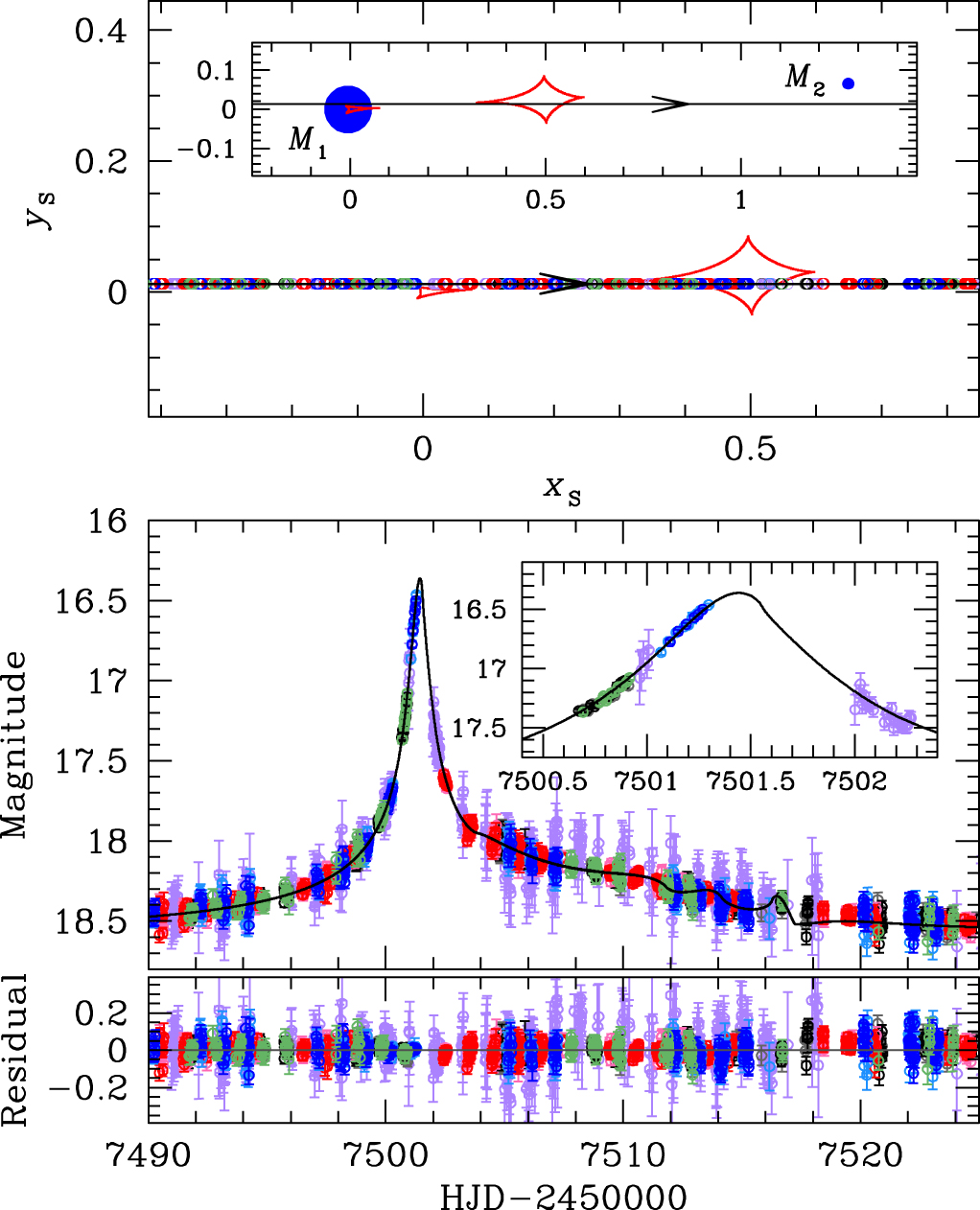

[Reproduction of Jung et al. (2017), Figure 3] Geometry and lightcurve of the binary lens model. Top: The upper panel shows the geometry of the binary lens model. The straight line with an arrow is the source trajectory, red closed concave curves represent the caustics, and blue filled circles (marked by $M_1$ and $M_2$) are the binary lens components. All length scales are normalised by the Einstein radius. The inset shows the general view and the major panel shows the enlarged view corresponding to the lightcurve of the lower panel. The open circle on the source trajectory is the source position at the time of observation whose size represents the source size. Bottom: The lower panel shows the enlarged view of the anomaly region. The inset shows a zoom of the lightcurve near $\rm{HJD}'\sim7501.4$. The curve superposed on the data is the best-fit binary lens model. |

The magnification model has the same parameterisation as the single lens model, except the flux model is a sum of two single-source magnifications multiplied by the flux of the source they are lensing: $$ \mathbf{F}=\mathbf{A_1}F_{\rm S1}+\mathbf{A_2}F_{\rm S2}+F_{\rm B}, $$ where $\mathbf{A_1}$ and $F_{\rm S1}$ are the primary-source magnification model and flux, $\mathbf{A_2}$ and $F_{\rm S2}$ are the secondary-source magnification model and flux, $F_{\rm B}$ is the blend flux, and the models $\mathbf{A_1}$ and $\mathbf{A_2}$ share the same physical lens parameters $(D_{\rm L},,M_{\rm L})$.

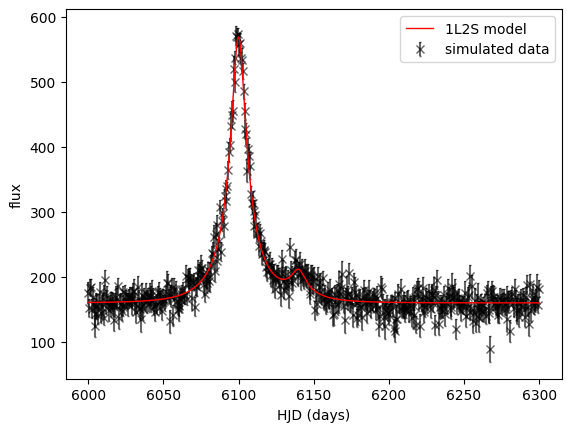

We can see the model in practice in the code cell below:

# A simulated binary source event

t01, u01 = 6100., 0.2 # primary source model parameters

t02, u02 = 6140., 0.2 # secondary source model parameters

t_E = 25. # tE is not necessarily the same, due to orbital motion of the lens system, but we would expect

# tE to be mostly due to the relative propermotion of the lens and source systems.

flux1, flux_ratio, blend_flux = 100., 0.1, 50.

n = 500 # number of data points

time = np.linspace(6000., 6300., n) # "data" epochs

N = 1000 # model plotting precision

T = np.linspace(6000., 6300., N) # model time array

# building the individual magnification models for each source star

model1 = mm.Model({'t_0': t01, 'u_0': u01, 't_E': t_E})

A1 = model1.get_magnification(time)

model2 = mm.Model({'t_0': t02, 'u_0': u02, 't_E': t_E})

A2 = model2.get_magnification(time)

flux = A1 * flux1 + A2 * flux1*flux_ratio + blend_flux

flux_err = 3.0 *(np.abs(5.0 + np.random.normal(size=n))) # flux uncertainties with mu=15 and std=3

error = flux_err * np.random.normal(size=n) # offset the "meaasurments" by an amount that is dependent

flux += error # on the uncertainty

data = [time, flux, flux_err]

my_dataset = mm.MulensData(data, phot_fmt='flux')

plt.close(1)

plt.figure(1)

# Plot the data

plt.errorbar(time, flux, yerr=flux_err,

fmt='x',

ecolor='k',

capsize=1,

color='k',

alpha=0.6,

zorder=0,

label='simulated data'

)

# Plot the model

F = model1.get_magnification(T) * flux1 + model2.get_magnification(T) * flux1*flux_ratio + blend_flux

plt.plot(T, F,

color='r',

linestyle='-',

lw=1,

zorder=1,

label='1L2S model'

)

plt.legend()

plt.xlabel(r'HJD (days)')

plt.ylabel(r'flux')

plt.show()

The measure of how far the data are from the model solution, scaled by the data uncertainties ($\chi^2$), is calculated using $$ \chi^2 = \sum\limits_i \frac{\left(F_i - x_i\right)^2} {\sigma_i^2}. $$ $\chi^2$ quantifies how likely a parameter set is to have generated the observed data, for a given model.

Similar to the procedure in the Single Lens notebook, the maximum likelihood solution $(F_{\rm S1}, F_{\rm S2}, F_{\rm B})$ can therefore be found by solving for the minima of this function. As in the previous section, the minima occurs where the partial derivatives of the $\chi^2$ function are 0; $$ \frac{\partial\chi^2}{\partial F_{\rm S1}} = 0, \frac{\partial\chi^2}{\partial F_{\rm S2}} = 0, \frac{\partial\chi^2}{\partial F_{\rm B}} = 0. $$ This linear regression problem can be written in the form $$ \begin{matrix} \begin{bmatrix} \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{1,i}^{2}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} & \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{1,i}A_{2,i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} & \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{1,i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} \ \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{1,i}A_{2,i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} & \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{2,i}^{2}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} & \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{2,i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} \ \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{1,i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} & \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{2,i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} & \sum\limits_{i}\frac{1}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} \end{bmatrix} & \times & \begin{bmatrix} F_{\rm S1} \ F_{\rm S2} \ F_{\rm B} \end{bmatrix} & = & \begin{bmatrix} \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{1,i}x_{i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} \ \sum\limits_{i}\frac{A_{2,i}x_{i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} \ \sum\limits_{i}\frac{x_{i}}{\sigma_{i}^{2}} \end{bmatrix} \ \mathbf{B} &\times& \mathbf{\Theta} &=& \mathbf{C}, \end{matrix} $$

which is solved following as follows: $$ \mathbf{\Theta} = \mathbf{B}^{-1} \mathbf{C} = \frac{adj,\mathbf{B}}{\det\mathbf{B}} \cdot \mathbf{C}. $$

Exercise 1

Use linear regression to determine the flux of the primary source, secondary source, and blend stars. Did you get out something similar to what you put in?

You may want to consider using functions from the numpy.linalg module.

# objective function

def binary_source_chi2(theta: np.ndarray,

model1: mm.Model,

model2: mm.Model,

data: List,

verbose: Optional[bool] = False,

return_fluxes: Optional[bool] = False

) -> float:

"""

chi2 function for a binary-source, single-lens, microlensing model.

Parameters

----------

theta : np.ndarray

Array of model parameters being fit.

model1 : mm.Model

Primary source model.

model2 : mm.Model

Secondary source model.

data : list

List of data arrays.

verbose : bool, optional

Default is False.

Print the primary source flux, secondary source flux, and blend flux.

Returns

-------

float

The chi2 value.

Notes

-----

The model parameters are unpacked from theta and set to the model1 and model2 parameters.

model1 and model2 are MulensModel.Model objects; see MulensModel documentation

(https://rpoleski.github.io/MulensModel/) for more information.

"""

#unpack the data

t, flux, flux_err = data

# model parameters being fit

labels = ['t_0', 'u_0', 't_E']

# change the values of model.parameters to those in theta.

theta1 = theta[:3]

theta2 = theta[3:]

for (label, value1, value2) in zip(labels, theta1, theta2):

setattr(model1.parameters, label, value1)

setattr(model2.parameters, label, value2)

# calculate the model magnification for each source

A1 = model1.get_magnification(t)

A2 = model2.get_magnification(t)

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE1.txt

#----------------------

FS1, FS2, FB = 0, 0, 0

######################

# print the flux parameters

if verbose:

print(f"Primary source flux: {FS1}")

print(f"Secondary source flux: {FS2}")

print(f"Blend flux: {FB}")

# calculate the model flux

model_flux = A1 * FS1 + A2 * FS2 + FB

chi2 = np.sum(((flux - model_flux) / flux_err)**2)

# In case something goes wrong with the linear algebra

if np.isnan(chi2) or np.isinf(chi2):

print(f"NaN or inf encountered in chi2 calculation: theta={theta}, chi2={chi2}")

return 1e16

if return_fluxes:

return chi2, FS1, FS2, FB

else:

return chi2

# generative model parameters

t01, u01 = 6100., 0.2

t02, u02 = 6140., 0.2

t_E = 25.

theta = np.array([t01, u01, t_E, t02, u02, t_E])

# initial chi2 value (will print the fluxes)

chi2 = binary_source_chi2(theta, model1, model2, data, verbose=True)

# generative fluxes

# source 2 flux used to generate the data

flux2 = flux1 * flux_ratio

print('\nprimary source flux used to generate the data:', flux1)

print('secondary source flux used to generate the data:', flux2)

print('blend flux used to generate the data:', blend_flux)

Primary source flux: 0

Secondary source flux: 0

Blend flux: 0

primary source flux used to generate the data: 100.0

secondary source flux used to generate the data: 10.0

blend flux used to generate the data: 50.0

The noise we generated in the light curve should mean that, even though we used the "true" magnification-model parameters, the flux values we retrieve are not exactly the same as those we used to generate the lightcurve. But they should be close (i.e. within a few flux units). If you got values that are wildly different something has gone wrong. It could be a fluke, so start be regenerating your noisy data. If that doesn't fix the problem you will need to take another look at your $\chi^2$ function (Exercise 1).

Exercise 2

Make an initial guess at the parameters for this model.

I know, we know them. Pretend we don't, okay.

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE2.txt

#----------------------

t01 = 0

t02 = 0

u01 = 0

u02 = 0

tE1 = 0

tE2 = 0

theta0 = [t01, u01, tE1, t02, u02, tE2]

######################

Next we are going to try fitting the data. Even though the likelihood space for a binary-source model should be reasonably well behaved, we will fit this simulated event using MCMC (emcee), because we want to take a look at the posteriors from the fit, so that we can understand if there are any degeneracies between magnification-model parameters. We can use emcee to both fit and collect our posterior samples.

If that all sounded like a forgein language to you, you might need to check-out, or revist, the Modelling notebook.

Exercise 3

Apply some reasonable bounds on the magnification-model parameters (theta).

Replace "True" with your conditions for what constitutes unresonable model-parameter values.

def ln_prob(theta: np.ndarray, model1, model2, data) -> float:

"""log probability"""

lp = 0.0

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE3.txt

#----------------------

# Implement the priors

if True:

return -1e16

######################

else: # the proposed parameters values are reasonable

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE7.txt

#----------------------

# Add a constraint (prior) on the blend flux

chi2 = binary_source_chi2(theta, model1, model2, data, return_fluxes=False)

######################

# return the log probability

return -0.5 * chi2 + lp

# starting lnL

lnP = ln_prob(theta0, model1, model2, data)

print('initial log probability:', lnP)

initial log probability: -1e+16

This model is pretty simple. It shouldn't take too long to converge; 1000 steps should be more than enough.

Exercise 4

Set up the emcee sample by choosing the fitting parameters you would like to use.

Note. there is only one correct value for ndim, but the other parameters are more nebulous.

# emcee parameters

nsteps = 1000

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE4.txt

#----------------------

# Replace these with your values

nwalkers = 0

ndim = 0

steps_between_plot_updates = 0

######################

# Set up the sampler

sampler = emcee.EnsembleSampler(nwalkers, ndim, ln_prob,

args=[model1, model2, data])

Exercise 5

Create an initial state for you walkers.

Note. These should be "random" values, close to your initial guess; the walkers should start in a hyper-dimensional ball in parameter space, about the inital guess. You might want to consider the np.random.randn function.

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE5.txt

#----------------------

# Initialize the walkers

initial_pos = 0

######################

# Function to update the plot

def update_plot(sampler, nwalkers, fig, axes):

ylabels = [r'$t_{0,1}$', r'$u_{0,1}$', r'$t_{\rm{E},1}$',

r'$t_{0,2}$', r'$u_{0,2}$', r'$t_{\rm{E},2}$',

r'$\ln{P}$']

for j in range(ndim):

axes[j].clear()

for i in range(nwalkers):

axes[j].plot(sampler.chain[i, :, j], 'k', alpha=0.1)

axes[j].set_ylabel(ylabels[j])

axes[ndim].clear()

for i in range(nwalkers):

axes[ndim].plot(sampler.lnprobability[i], 'r', alpha=0.1)

axes[ndim].set_ylabel(ylabels[ndim])

axes[ndim].set_xlabel('step')

clear_output(wait=True)

display(fig)

fig.canvas.draw()

fig.canvas.flush_events()

def run_emcee(sampler: emcee.EnsembleSampler,

initial_pos: np.ndarray,

nsteps: int,

steps_between_plot_updates: int,

nwalkers: int,

ndim: int,

verbose: Optional[bool] = True

) -> Tuple[emcee.EnsembleSampler, np.ndarray]:

"""

Run the emcee sampler and update the plot.

Parameters

----------

sampler : emcee.EnsembleSampler

The sampler object.

initial_pos : np.ndarray

The initial position of the walkers.

nsteps : int

The number of steps to run the sampler.

steps_between_plot_updates : int

The number of steps between plot updates.

nwalkers : int

The number of walkers.

ndim : int

The number of dimensions.

verbose : bool, optional

Default is False.

Print the progress of the sampler.

"""

# Create the figure and axes

fig, axes = plt.subplots(ndim + 1, 1, figsize=(10, 15));

# Run the sampler in steps and update the plot

i = 0

while i < nsteps:

if i == 0:

state = sampler.run_mcmc(initial_pos, steps_between_plot_updates, progress=verbose)

else:

state = sampler.run_mcmc(state, steps_between_plot_updates, progress=verbose)

update_plot(sampler, nwalkers, fig, axes)

i += steps_between_plot_updates

clear_output(wait=True) # extra stuff to stop the notebook displaying the final plot twice

# Access the final state

final_state = sampler.get_last_sample().coords

return sampler, final_state

# Run the sampler

sampler.reset() # reset the sampler (you will need this if you want to run_emee fresh, from initial_pos)

sampler, final_state = run_emcee(sampler, initial_pos, nsteps,

steps_between_plot_updates, nwalkers, ndim)

# continue running (use this if you want more steps after the first run)

#sampler, final_state = run_emcee(sampler, final_state, nsteps,

# steps_between_plot_updates, nwalkers, ndim)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[8], line 73

71 # Run the sampler

72 sampler.reset() # reset the sampler (you will need this if you want to run_emee fresh, from initial_pos)

---> 73 sampler, final_state = run_emcee(sampler, initial_pos, nsteps,

74 steps_between_plot_updates, nwalkers, ndim)

76 # continue running (use this if you want more steps after the first run)

77 #sampler, final_state = run_emcee(sampler, final_state, nsteps,

78 # steps_between_plot_updates, nwalkers, ndim)

Cell In[8], line 59, in run_emcee(sampler, initial_pos, nsteps, steps_between_plot_updates, nwalkers, ndim, verbose)

57 while i < nsteps:

58 if i == 0:

---> 59 state = sampler.run_mcmc(initial_pos, steps_between_plot_updates, progress=verbose)

60 else:

61 state = sampler.run_mcmc(state, steps_between_plot_updates, progress=verbose)

File /opt/hostedtoolcache/Python/3.11.13/x64/lib/python3.11/site-packages/emcee/ensemble.py:450, in EnsembleSampler.run_mcmc(self, initial_state, nsteps, **kwargs)

447 initial_state = self._previous_state

449 results = None

--> 450 for results in self.sample(initial_state, iterations=nsteps, **kwargs):

451 pass

453 # Store so that the ``initial_state=None`` case will work

File /opt/hostedtoolcache/Python/3.11.13/x64/lib/python3.11/site-packages/emcee/ensemble.py:315, in EnsembleSampler.sample(self, initial_state, log_prob0, rstate0, blobs0, iterations, tune, skip_initial_state_check, thin_by, thin, store, progress, progress_kwargs)

313 state_shape = np.shape(state.coords)

314 if state_shape != (self.nwalkers, self.ndim):

--> 315 raise ValueError(f"incompatible input dimensions {state_shape}")

316 if (not skip_initial_state_check) and (

317 not walkers_independent(state.coords)

318 ):

319 raise ValueError(

320 "Initial state has a large condition number. "

321 "Make sure that your walkers are linearly independent for the "

322 "best performance"

323 )

ValueError: incompatible input dimensions (1, 1)

*Write your answer here.*

Why don't we take a look at the flux parameters for the final state and see if we can figure out what is going on?

# corner-like scatter plot of final state: u02, t02, FS2, FB

def plot_corner(final_state: np.ndarray,

model1: mm.Model,

model2: mm.Model,

data: list,

figure_number: Optional[int] = 3

) -> None:

"""

Plot the corner-like scatter plot of the final state.

Parameters

----------

final_state : np.ndarray

Array of final state parameters.

model1 : mm.Model

Primary source model.

model2 : mm.Model

Secondary source model.

data : list

List of data arrays.

figure_number : int, optional

Default is 3.

The figure number.

"""

# labels

labels = [r'$t_{0,1}$', r'$u_{0,1}$', r'$t_{E,1}$', r'$t_{0,2}$', r'$u_{0,2}$', r'$t_{E,2}$', r'$F_{S,1}$', r'$F_{S,2}$', r'$F_B$']

# collect the data dor plotting

corner_array = np.zeros((len(final_state), ndim + 4))

corner_array[:, 0:ndim] = final_state

for i in range(len(final_state)):

chi2, FS1, FS2, FB = binary_source_chi2(final_state[i], model1, model2, data, return_fluxes=True)

corner_array[i,ndim] = FS1

corner_array[i,ndim + 1] = FS2

corner_array[i,ndim + 2] = FB

corner_array[i,ndim + 3] = chi2

# plot

plt.close(figure_number)

plt.figure(figure_number)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(ndim + 3, ndim + 3, figsize=(15, 15))

for i in range(ndim+3):

for j in range(ndim+3):

if i > j: # plot the scatter plots

scatter = axes[i, j].scatter(corner_array[:, j],

corner_array[:, i],

c=corner_array[:, -1],

cmap='viridis_r',

s=0.5

)

if i == ndim + 2:

axes[i, j].set_xlabel(labels[j])

else: #turn of ticks labels

axes[i, j].set_xticks([])

if j == 0:

axes[i, j].set_ylabel(labels[i])

else: #turn of ticks labels

axes[i, j].set_yticks([])

elif i == j: # plot the histograms

axes[i, j].hist(corner_array[:, j], bins=20, color='k')

if i == ndim + 2:

axes[i, j].set_xlabel(labels[j])

else:

axes[i, j].set_xticks([])

axes[i, j].set_yticks([])

else: # turn off the upper triangle of axis

axes[i,j].axis('off')

# Add the colorbar using the scatter plot object

cbar = fig.colorbar(scatter, orientation='horizontal', ax=axes, aspect=100)

cbar.set_label('chi2')

plt.show()

plot_corner(final_state, model1, model2, data)

Do you see the problem? Negative blend-flux values are allowing for overly high $F_{\rm{S},2}$ values, in combination with correspondong low $t_{\rm{E},2}$ and high $u_{0,2}$. We can avoid this problem by not allowing negative blending, which, considering our data was generated without using photometry, makes absolutely no sense. For events found in real data a small negative flux can be plausible as it is an indication that the "zero flux" background-level in the photometry was actually measuring some flux from stars. In these cases, the blend flux should actually have been measured as very small or 0.

Exercise 7

Add a prior on blend flux in ln_prob() function (Exercies 3) and any other additional priors you think seem reasonable.

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE8.txt PART: 1

#----------------------

# re make the sampler (Make sure to run the ln_prob cell after you edit it)

# rerun the sampler

######################

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE8.txt PART: 2

#----------------------

# corner plot

######################

# Plot the lightcurve

plt.close(8)

plt.figure(8)

######################

# EXERCISE: BinarySourceE8.txt PART: 3

#----------------------

# Your code goes here

######################

plt.show()

*Write your answer here.*

Binary source events can throw a real spanner in the works when it comes to event modelling. Binary sources complicate what is already a very complicated analysis process and the binary source model is full of correlated parameters that make it hard to determine the true values precisely. Not only can they mimic caustic purturbations with a finite source effect, but they can also mess with colour-colour inference between observatories such as contemporaneous space-based observations, or late-time follow-up lens-flux and astrometric observations. With binaries possibly making up 40% or more of the stars in the Galactic centre (Gautam et al., 2024; McTier, Kipping, & Johnston, 2020), this potential complication is not one that should be ignored.

Having a binary source in a microlensing event can double the number of parameters in our models, which has a dramatic impact on compute time. If we are calling a magnification function for each source, then the compute time roughly doubles for each model evaluation, as the magnification function is usually the most computationally intensive piece of microlensing event-modelling code. Besides which, higher dimensions of parameter space simply take longer to explore.

These real costs are part of the reason for why microlensing simulations, to date, mostly ignore binary sources. Recent work by the PopSyCLE team (Abrams et al., 2025) found that, using their population models, 55% of observed microlensing events involve a binary system;

14.5% wth a single source and muptiple lenses,

31.7% with multiple sources and a single lens, and

8.8% with multiple sources and multiple lenses.

This paper is well worth a read, if you have the time.

Exercise 10

Which binary-lens models do you think would have degenerate, binary-source, counter parts?

*Write your answer here*

Recent simulations by Sangtarash & Yee (2025) demonstrated that, for Roman-like cadences, the binary-source/wide-orbit-planet degeneracy is most persistent when $\rho$ is large (which typically occurs in events with small $\theta_{\rm E}$) or $q$ is small, as the likelihoods of the models do not differ significantly in these cases; we can infer that, in general, lower-mass objects make this degeneracy harder to resolve.

As a closing statement for this notebook lets simplify what we have learned to this TLDR:

Next steps#

Well, you've been warned. Now let's move on to something else. Maybe to one of these:

Binary lenses (comming soon - see dev brach)

Higher-order effects (release TDB)

The Galactic model (release TDB)

Okay, bye. I'll see you there.